Muppet Week has been a fun diversion for us here in the Tor.com office. (And, we hope, for you as well.) We’ve gone batty over the various Muppet movies, from old to new, looked at old science fiction television greats who have partied with the Muppets, enjoyed Farscape, Labyrinth, and The Dark Crystal, and pondered how the world might have been changed if Henson hadn’t gravitated towards puppets.

Some of these articles were just excuses to write about Muppets. (I mean, c’mon, MUPPETS.) But underneath that enthusiasm was an urge to reveal just how much Jim Henson was interested in exploring other worlds. Underneath his large forays into fantasy were a host of small details, little nudges and influences, that echo the same kind of fascination that we have with genre as readers.

From the outset, the concept of masking yourself inside of a bright puppet brings to mind the same kind of embodiment one gets when reading high fantasy or science fiction. When you see yourself as a character in a fictional world it’s far easier to express yourself and your wishes. Henson chose puppets as a creative outlet for somewhat mercenerary reason—they were the quickest means to an end, but even before that Henson was interested in pushing the boundaries of what was considered real. Witness an early effort in this clip from his Academy Award-nominated surreal short film Time Piece.

He would follow up on this line of experimental media four years later in The Cube, a short film which proposes a world where the fourth wall is aggressively broken between television shows and their viewers.

Testing the boundaries of this world eventually led Henson to create entirely new worlds of his own. This is most vividly experienced in The Dark Crystal, a movie which came about after Henson was inspired by the British countryside and the artwork of Brian Froud into imagining a completely different fantasy setting. (Definite shades of Tolkien and Neil Gaiman there.) Henson effectively built the world of Dark Crystal in his head, piece by piece, until he had enough to wind a narrative through. Hence, the overload of exposition in the film itself. Henson fell into a common trap that many fantasy writers fall prey to: being so proud of their world that they overexplain it.

Henson slid from hard epic fantasy to a more boundless fairytale setting with Labyrinth. Whereas Dark Crystal was motivated by the circumstances of its world, Labyrinth was motivated by the personal growth of its main character, focusing particularly on the magic of transition. Transitions between worlds and the transitions in maturity that we experience in life. In the movie, Sarah is pulled between her childhood desires and the allure of adulthood and the synthesis that she ultimately forms from them is inspiring. She takes on the added responsibilities that come with being an adult while refusing to accept that this means the rejection of fantasy. The two can co-exist and, if Henson’s entire career is any indication, must co-exist.

The late 80s brought Henson’s fascination with other worlds to the small screen and he began exploring and reinterpreting the fantasy worlds of others. This time he was joined by his daughter Lisa, who had recently graduted Harvard with a focus on folkore and mythology, and the two set about to work on The Storyteller series.

The initial Storyteller mini-series focused on retelling folk tales without glossing over their darker origins, in much the same manner of today’s Fables or the even newer Grimm. The Storyteller hewed to the oral tradition of passing these tales along by framing every episode with a Narrator. (This commentary device in and of itself is a common trope in Henson works, from Statler and Waldorf to more serious works like The Storyteller.)

While the initial mini-series focused on folklore, a second mini-series focused on Greek myths. (Both featured actors as the Narrators that, oddly enough, would go on to feature in the Harry Potter films. The first being John “Ollivander” Hurt and the Greek Myths Narrator being Michael “Dumbledore” Gambon.) Both mini-series are rich and detailed; regrettably we didn’t have time to get further into either series during Muppet Week. (Although that doesn’t mean we won’t some time down the line.)

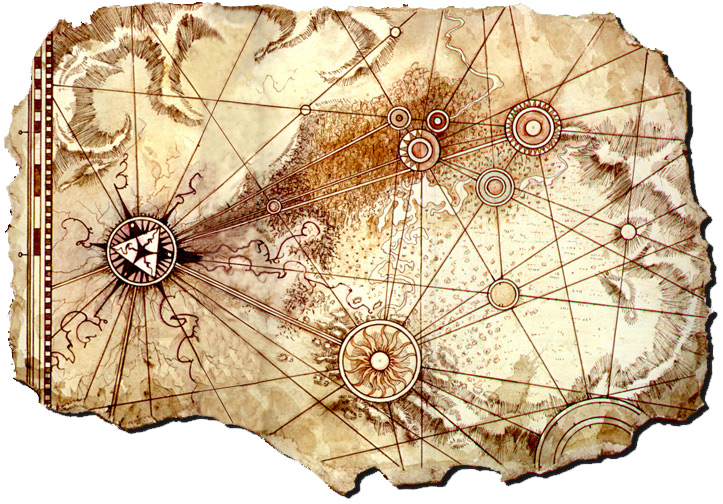

At this point, Henson Company projects would enter a period of literary reinterpretation. The Muppets themselves would journey through A Christmas Carol and Treasure Island, but it didn’t stop there. The Creature Shop, an independent entity that had been created solely to create The Dark Crystal, had since spun off from Henson and began to work on their own interpretation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland titled Dreamchild. Through his own actions, Henson was now inspiring others to explore new worlds.

Despite Jim Henson’s untimely death, the exploration never ceased. Take Farscape, or Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean’s Mirrormask, or the adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Witches, or The Fearing Mind, which stars Katee “Starbuck” Sackhoff right before her star turn on the new Battlestar Galactica. Jim Henson, his creations, and his legacy, are instrumental to the existence of these productions. They either could not exist without his exploration in SFF, or would exist in a vastly different form.

And that includes Star Wars. The Empire Strikes Back and The Dark Crystal shared crew to such an extent that when George Lucas needed a Yoda, Frank Oz was tapped by Henson. In turn, Lucas lent ILMs services to expanding and bringing visual depth to Henson’s subsequent film Labyrinth. Imagine Star Wars without Yoda or Labyrinth without, well, the labyrinth!

These are just the broad strokes of Henson’s work in science fiction and fantasy. There are numerous other smaller projects and factoids. The Henson Company itself provides a handy list here.

Want to learn more? If you’re in Atlanta or New York City, you can catch exhibits on Henson and his work at the Center for Puppetry Arts and the Museum of the Moving Image, respectively.

This post marks the end of Muppet Week, but not the end of the ongoing discussion. From the beginning, it seems that Henson was intrigued by science fiction and fantasy. So perhaps that is why we, as genre readers, are so intrigued by his creations?

Chris Lough is the production manager of Tor.com.

You left out the future Lord of Winterfell and heir to Gondor. Sean Bean makes an apperance in one of the Storyteller episodes

@1 Beefy Bean? Really? That is tops.

Yeah I think it’s The True Princess, or something, anyway he plays a prince. Found it when watching this on Netflix and did a double take becaus he is just so… un-Bean like in it, what with the happy and the prancing.

Indeed. One does not simply prance into Mordor.

Thanks for doing this Muppet Week, although I kinda wish it had been a month! :)

I love The Storyteller, and I’ve always wished that they would go back and do another series of those, maybe with an Asian twist to them.

Jim was always very pleasant to work with. I worked as a cameraman on the original pilot and many shows at ATV Elstree and last saw him when walking over Hampstead Heath some years later when we had a chat. A sad loss to showbiz.